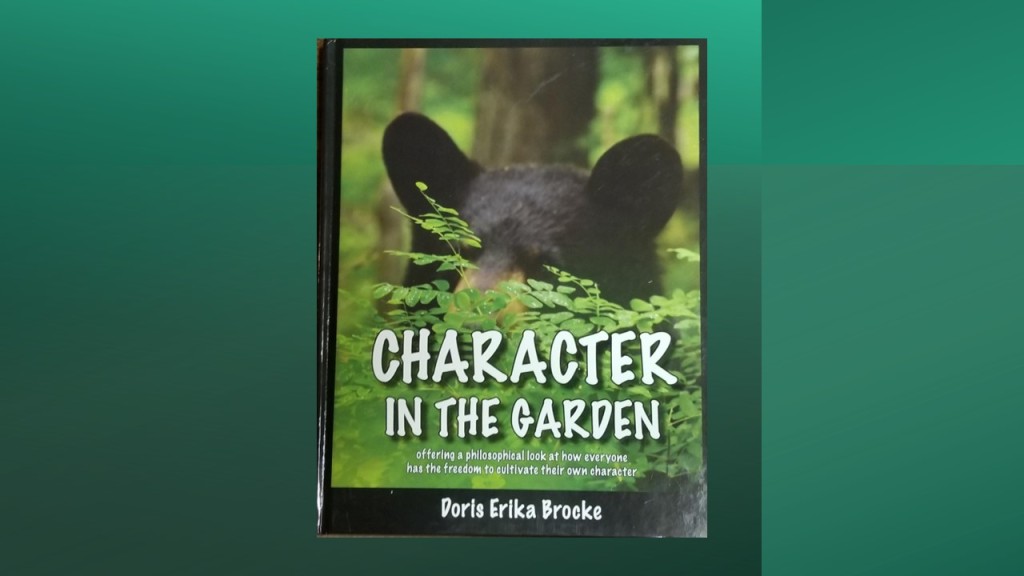

Character in the Garden, Doris Erika Brocke. Brocke House Enterprises (ISBN: 9780991835515), 2021.

Summary: A compilation of photographs from the author’s surroundings combined with quotations focusing on the qualities of character.

Doris Erika Brocke and her husband Dale live in northeast British Columbia. Both are photographers and gardeners. Dale is also a stained glass artist and Doris a writer. Doris has entertained a dream for fifty years of writing a book on character. In Grade 5 she was given a Gideon’s Bible with a list of character qualities and associated Bible verses. Twenty-eight virtues in all. Over the years, she used this list to examine her own character and how she might improve as a person. And she dreamed about writing a book about these qualities, a dream realized in this book.

She created a book that combines so many facets of her life: the place where they live with its gorgeous gardens and woodland surroundings, stunning photography by her and her husband, a plethora of quotations organized by character qualities, and shaped by the faith and love shared by the two of them.

The book begins with an introduction and five sections on thoughts, purpose, actions, habits, and character. This is followed by twenty-eight sections ordered alphabetically of those Gideon Bible character traits beginning with Cheerfulness and ending with Truthfulness. The book concludes with five more sections on nature, trees, God, destiny, and death. Each page has one to four photographs paired with quotes. Sometimes a quote will be set aside on its own. Quotations are drawn from the Bible and writers from Augustine to Voltaire. An index at the end lists authors alphabetically.

The photographs feature various animals from squirrels to deer and moose. There are a number of exquisite shots of hummingbirds, butterflies, and bees on flowers of every imaginable species. I love one of a bumblebee covered in hollyhock pollen under the section on “Honor.” In his diligence, this bee truly has covered himself in a kind of honor. That brings me to an observation. Each section on character uses a number of photographs of the same type of flower, bird, animal, etc. The section on “honor features hollyhocks, The one on “Patience” focuses on apples–I guess patience is involved in awaiting their ripening. And of course, “Love” features deep red roses. The bleeding heart photographs in the section on “Discretion” were exquisite.

If I were try to capture for you all the quotes I loved from this book, it would be a very long review. I will share one I particularly appreciated by Iris Murdoch:

“Love is the very difficult understanding that something other than yourself is real.”

I’ll be thinking of that for a while.

This book is a feast for the eyes and nourishment to the heart. There is so much wrong in the world, so much devastation, and so much deceit, that we may quickly lose sight of goodness, truth, and beauty. Yet many people of character quoted in this book distinguished themselves as they upheld goodness, truth, and beauty amid the world’s troubles. Often, the virtues they displayed were cultivated in the “hidden years” or even failure experiences. We so need works like these that focus on the goodness we would cultivate in our lives and relationships, the truths we will live by, and the beauty around us that inspires us and which, in turn, we must tend and protect.

I’ll leave the final words on this book to the author and others who have read the book.

____________________

Disclosure of Material Connection: I received a complimentary copy of this book from the author for review. It was deeply appreciated!